Ministry

‘Baptized Capitalism’

According to Cru’s website, its mission is to “win, build and send Christ-centered multiplying disciples.” Likewise, its stated vision is to see “movements everywhere, so that everyone knows someone who truly follows Jesus.” Interviews with over 30 former members reveal troubling patterns in Cru’s attempts to achieve these goals.

Prior to 2011, Cru was known as Campus Crusade for Christ. It changed its name in part due to offensive connotations with the word “crusade,” particularly to Muslims.

But its mission remained the same — a vigorous evangelical campaign designed to bring about mass religious conversion.

Cru can be found on college and high school campuses across the nation, each chapter charged with the mission of spreading religious beliefs promising eternal salvation.

While its headquarters are located within an enormous compound in a quiet corner of Orlando, Florida, each campus chapter of Cru is primarily operated by college students and recent graduates — often young married couples — who act as staff and student leaders, according to multiple former members. Cru provides the leadership team with pamphlets and written materials to guide their campus activities.

Campus Cru chapters hold group meetings every Thursday where students gather to sing worship songs, pray, and listen to religious speakers. Large group meetings are supplemented by gender-specific small group meetings where students discuss the Bible in a more intimate setting. There are also “training groups” and “action groups” for students interested in becoming more heavily involved in Cru.

Cru looks slightly different on each campus, as the environment can be affected by the host school and region’s culture. A chapter of Cru at West Virginia University’s campus, for example, might be run less formally or expect less rigorous Bible studies than a chapter at Cornell University. However, all Cru chapters share two common focuses: accountability and recruitment.

Cru encourages students to hold each other accountable for exhibiting biblical values like spending time reading the Bible, sharing their faith with other students, and remaining “sexually pure.” Students are encouraged to confess to each other when they fall short. They are assigned “disciplers” who meet with them weekly to discuss their spiritual health.

Former member Fred Harrell attended Cru at the University of Florida from 1980 to 1985. He described the group as practicing “baptized capitalism,” calling Cru’s cookie-cutter approach to ministry “formulaic” and “a denial of the individual.”

A former Cru member from Cornell University, who wished to remain anonymous for privacy reasons, recalled being encouraged to invite all of their friends to join Cru. The culture at Cru, they said, was charismatic and welcoming. They said the mantra they heard from Cru was, “Make it a party –- but also, Jesus.”

Missionary trips as colonizing conversions

Students in Cru are encouraged to go on mission trips multiple times a year with the goal of proselytization. Shorter summer mission trips could involve traveling to another campus’s Cru chapter — or spending a weekend attempting to convert day-drinking spring-breakers in places like Myrtle Beach, South Carolina.

According to several former members, these beach trips sometimes feel more like vacations than mission trips. Other former members said their trips were overtly advertised as vacations with a touch of evangelism on the side. They said they felt cheated when those trips sometimes involved hard labor.

Matt Brewer was active with Cru at the University of Mississippi from 2005 to 2010. Brewer is a gay man who said he experienced sexual solicitation and harassment from multiple Cru members during his time with the organization.

Brewer said Cru leadership would attempt to persuade him to go on mission trips to other campuses by saying he was exactly the right person for the job and promising him a myriad of “perks.” If Brewer needed gas, money, food, or a place to stay, Cru said it would provide for him — as long as he agreed not to tell anyone about his troubling experiences with staff.

Larger Cru mission trips took student missionaries to other countries, regardless of the fact that their presence was not always legal.

Rebecca Carey served on Cru’s staff at the University of Texas in San Antonio from 2015 to 2017. They participated in a 2016 mission trip to East Asia with Cru.

Carey said Cru missionaries are regularly sent to countries like China “under the guise of studying abroad with an emphasis on cultural exchange,” but then proceed to violate foreign laws by openly evangelizing.

The Chinese government has laws in place criminalizing missionary work unless the religious organization is “lawfully registered within Chinese territory,” according to China’s National Religious Affairs Administration.

No data could be found to confirm whether Cru is registered to evangelize in China, but multiple former members’ experiences suggest Cru takes great care to ensure its students are not identifiable as missionaries.

Cru trains student missionaries to fall back on step-by-step programs like the KGP: Knowing God’s Plan to direct their conversations. Overseas missionaries are required to keep meticulous records detailing the number of these conversations they have with locals, according to former members.

The reason for this documentation is Cru’s hyper-fixation on quantifying its evangelism into hard numbers, former members said. Carey said their team in East Asia had to report the number of “gospel conversations” they had while abroad and the number of “conversions” they successfully made.

Meghan Crozier, a college professor who blogs about evangelical deconstruction, said conversion attempts are a pillar of evangelical Christian spaces like Cru. She described it as the “notion that we’ve got something that other people need to have, and we need to spread that to the world.

Former Cru missionaries reported there was minimal oversight of these international trips. A student missionary in France, for example, could set their own schedule and still receive a stipend (self-fundraised on their own time).

Moreover, some mission trips were constructed with a disregard for the student missionaries’ safety in mind, sending participants to countries where it was not only illegal to evangelize but was also frowned upon by locals.

Travis Eiler, who at the time was a recent graduate of Southern Wesleyan University, and was recruited by Cru to go on a missionary trip to Shymkent, Kazakhstan in 2011, where Muslims make up over 70% of the country’s population. According to the Central Asian Bureau for Analytical Reporting, Kazakhstan does not permit religious activities beyond state-run and state-controlled institutions.

Eiler’s Cru missionary team was told by staff to speak in code and pretend to have other reasons for being in the country. The dangers of evangelizing were not made clear to Eiler or his family, his parents said.

The 23-year-old Eiler was found deceased with a plastic bag over his head in his hotel room in Kazakhstan on Dec. 2, 2011. The cause of death was ruled asphyxiation. The FBI initiated an investigation.

“It’s my opinion that they’re training martyrs with reckless abandon,” said Eric Eiler, Travis’ father

The Eilers sued Cru for negligence. Their case was dismissed in court, and the FBI investigation fizzled out when the officer assigned to the case retired. Today, the Eiler family is still waiting for answers.

Cru’s national headquarters sit on a massive gated plot of land in Orange County, Florida. (Em Espey)

Former Cru member Rachel Duryea (left) and a friend sporting shirts from Cru’s chapter at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona.

(Courtesy of Rachel Duryea)

A team of women from California State Polytechnic University’s Cru chapter poses on the beach during a retreat. (Courtesy of Rachel Duryea)

Travis Eiler photographed abroad. Danielle Eiler, Travis’s mother, described the organization as having “a whole lot of money and a whole lot of power.”

(Courtesy of Danielle Eiler)

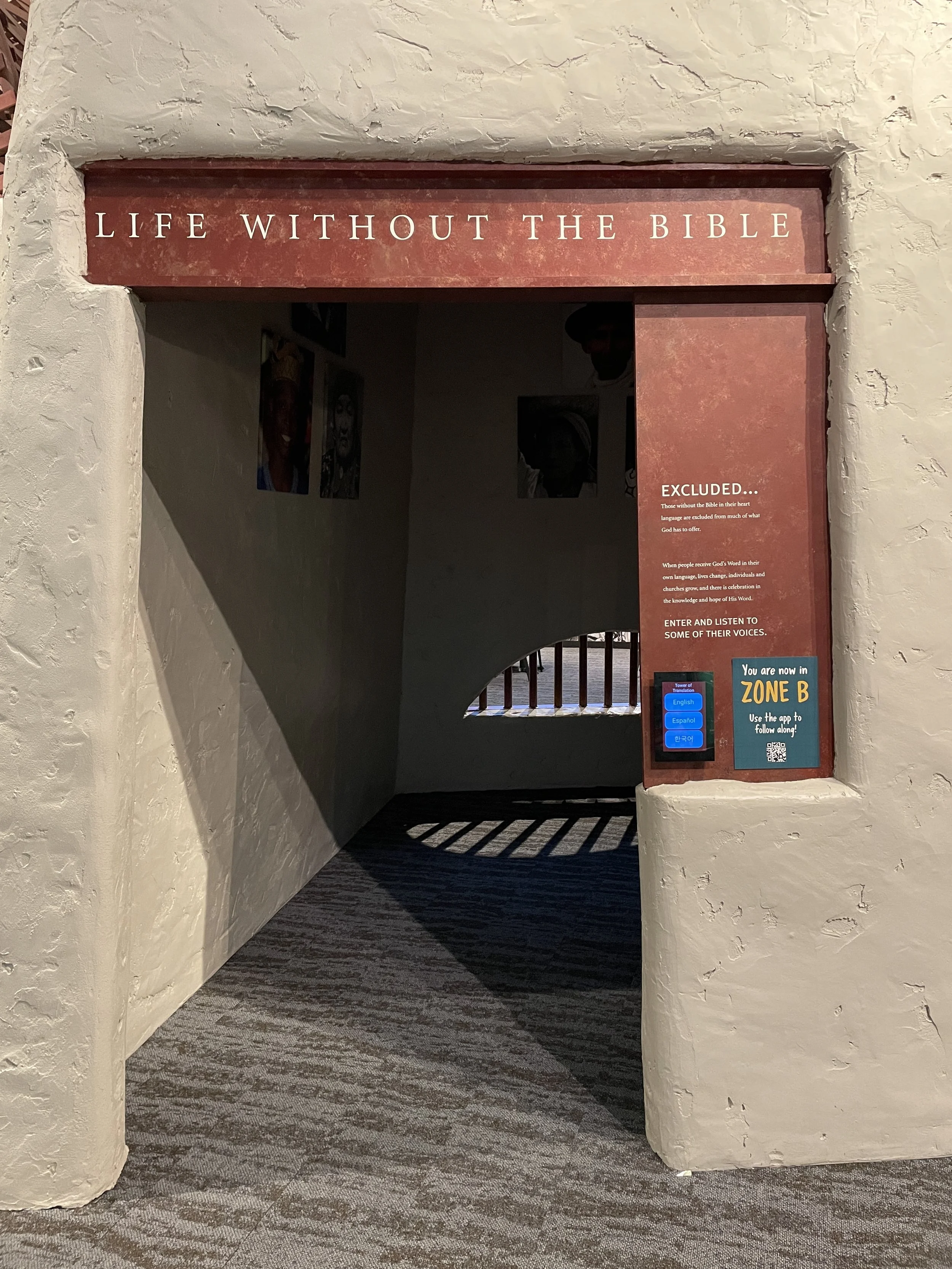

Exhibit from a Bible museum located in the Wycliffe Discovery Center, next door to Cru’s headquarters in Orlando. (Em Espey)

“Kids are going to believe whatever you tell them.”

— Zac Thompson, former Cru member