LGBTQ+ exclusion

It’s okay to be gay…kind of

In Cru’s early years, its leaders spoke candidly about their disdain for the LGBTQ+ community. Founder Bill Bright published a book in 1995 called The Coming Revival, in which he insists that “God has cursed those who insist on practicing and promoting homosexuality” and rails against gay activists ‘arrogantly demanding their ‘rights.’”

Today, Cru has shifted its rhetoric in response to heightened societal sensitivity to discrimination and homophobia. The organization has never released a formal position statement on LGBTQ+ issues, but applying the slightest scrutiny makes its position clear.

FamilyLife is a branch of Cru designed to provide resources for family and relationship issues. FamilyLife has published extensively on sexual orientation and gender identity, including a 2013 article titled “Why We Oppose Same-Sex Marriage.”

Cru itself provides members with a number of written resources and guidelines on how to approach sexuality from a Christian worldview. A Cru college-level course offered in January 2020 on “Christian Worldview and Ethics” taught by Western Seminary professor Todd L. Miles includes a module in its syllabus on “transgenderism” and “homosexuality.”

Rick James is a 35-year Cru veteran who serves as associate publisher of CruPress, Cru’s “publishing ministry.” In a 2015 revised edition of Flesh, a book designed to help Christian men navigate their sexual lives, James writes:

“Homosexuality is a disfigurement (a bentness or brokenness) of what God designed for sex, intimacy, and marriage. It is a bentness of attraction, and as we reflect our Father in heaven, that bentness is not to be lived out or reflected in our lives. I honestly wish there was some wiggle room here, but there just isn’t.”

Cru has previously collaborated with now-disgraced Exodus International, the largest conversion therapy organization in the United States. Several former members recall times when leaders from Exodus would visit their respective campus’s Thursday night Cru meetings to give promotional presentations about their work.

Cru regularly invites “ex-gay” speakers to attend their annual winter conferences and other events. Notable guests include Jackie Hill Perry, author of Gay Girl, Good God; Sam Allberry, author of Is God Anti-Gay?; and Brady Cone, a writer and speaker who is, in his own words, “in a heterosexual marriage” while still experiencing same-sex attraction from his “previous gay life.” Cone runs Calibrate Ministries, a company seeking to help men in Christian spaces pursue heterosexuality.

Tim Thompson, whose parents were Cru staff members for decades and who was heavily involved with Cru on his own campus, said homophobia is “baked into the DNA” of the organization.

“Even when they’re not talking about queerness or any spectrum thereof, they’re commenting on it by reinforcing heteronormative and patriarchal standards across everything,” Thompson said.

Hush-hush about homosexuality

Nowadays, Cru is hesitant to vocalize its opposition to same-sex couples. Rebecca Carey was involved with Cru during their time at the University of Texas at San Antonio from 2015 to 2017. They said it felt like Cru deliberately avoided addressing the topic of homosexuality.

“Unless you come forward with [homosexuality] being something you ‘struggle’ with,” Carey said, “that’s never explicitly stated.” At the same time, “They wouldn’t let anyone in an openly gay relationship or someone who didn’t think of homosexuality as a sin be on the leadership team.”

During her senior year, Carey befriended a lesbian student who expressed interest in checking out Cru, but only if Carey could assure her that she wouldn’t experience discrimination because she was gay. Carey tried to ask Cru staff members about it, but she said they “didn’t really have a good answer for me.” The staff recommended books by Jackie Hill Perry and Sam Allberry, Carey said, but would not confirm whether their friend would be welcomed.

Applying for a staff position with Cru requires students to answer invasive application questions about their personal life, including questions about the applicant’s childhood, medical history, mental health, relationship status and sexual activity. Students applying for a trip abroad must fill out a similarly comprehensive application.

Question 53 on the application form for an overseas trip reads: “Have you ever experienced same sex attraction? If yes, please elaborate.” The next question continues: ‘Have you ever been involved in a physical sexual experience with a member of the same sex? If yes, please elaborate.”

Chelsy Albertson is a digital designer, educator and researcher based out of Indiana who received her Master’s degree from Purdue University in December 2021. She’s also a lesbian who was closely involved with Cru on her undergraduate campus at Ball State University from 2004 to 2008. Albertson ultimately left Cru and wrote her Master’s thesis on “lesbian identity tension” within the organization. She interviewed 14 lesbian former Cru members for her thesis.

Many of Albertson’s study participants mentioned having to sign documents pledging their agreement to Cru’s beliefs about sexuality. One participant described receiving an 8-page document during staff orientation called “Leading in a Complex Moral Environment,” which outlines Cru’s stance on gender and sexuality.

Within the document, “same-sex sexual relations” appears alongside rape, sex trafficking, and incest in a laundry list of activities deemed sinful.

“We had to sign something saying we agreed with it by the end of the summer,” the participant told Albertson.

Multiple former Cru members have described people being turned down for leadership positions or mission trips because they were honest about their sexuality on application forms. Several said they were explicitly told the reason for their rejection related to their sexual orientation.

On more than one occasion, Cru has been found to be in direct conflict with college campus nondiscrimination policies because it refuses to allow LGBTQ+ students to hold leadership roles.

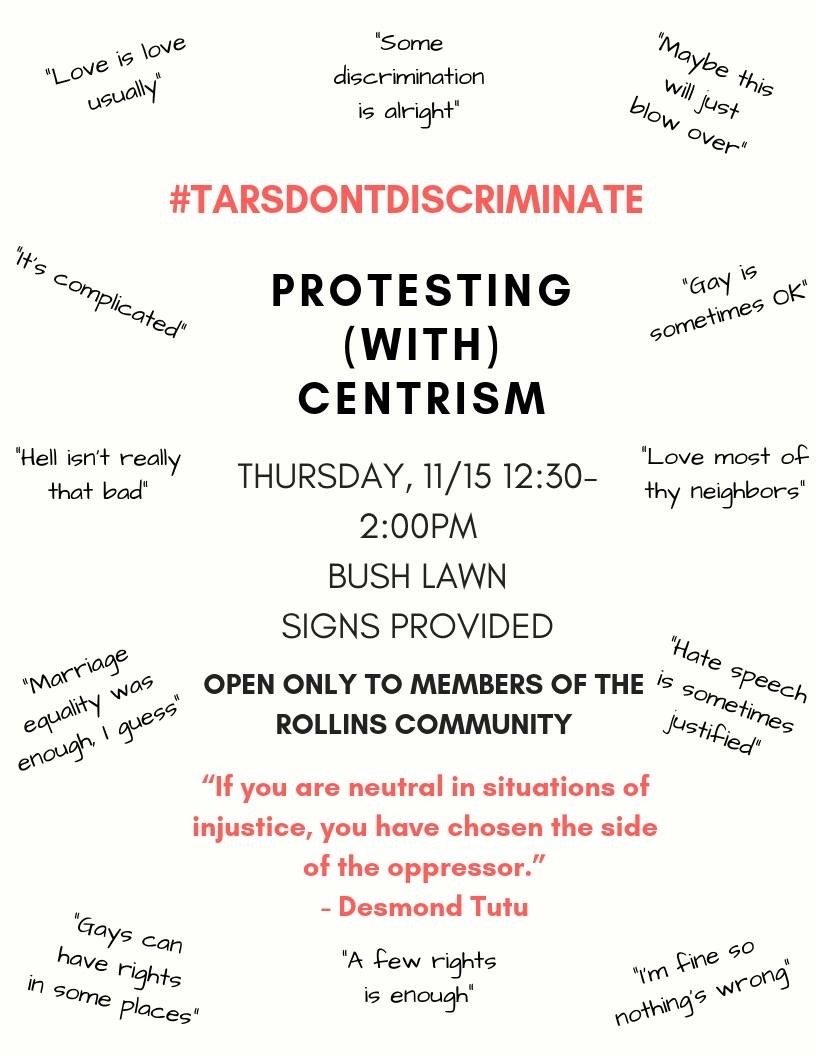

For example, Cru attempted to be recognized as a registered student organization on Rollins College campus in 2018 and faced intense backlash from the student body. Rollins president Grant Cornwell said Cru “explicitly waged a quiet campaign” to have the college’s nondiscrimination policy moderated because “in public opinion, they were the ones in disfavor.”

Over 285 people signed the student petition to uphold Rollins’ nondiscrimination policy as written. Cornwell said there was “no question” the majority of students supported holding Cru accountable to the nondiscrimination policy. Still, he described the situation as “ethically uncomfortable” for the college.

After an arduous six-month saga, Cru ultimately agreed to comply with Rollins’ nondiscrimination policy and, as of today, has an active presence on its campus.

Conditional community

Former Cru members consistently described how questioning Cru’s stance on LGBTQ+ issues often results in quiet rejection from Cru spaces and the denial of access to leadership opportunities.

Kiera Molloy attended College for Creative Studies, a small private art school in Detroit, and was involved with her campus’s branch of Cru from 2017 to 2020. At one point she participated in an all-female Cru “action group.” On their website, Cru describes action groups as “the people who have been bitten by the Great Commission bug and wouldn’t stay away if you paid them.”

Molloy’s group met weekly for check-ins and collaboration. During one of their weekly meetings, the question came up of what to do when someone asks what the Bible says about homosexuality.

Molloy said after the question was asked, “The room went quiet.” She said no one seemed to want to answer, so she spoke up and suggested that condemning people for their sexuality “is not a judgment we get to make.” At the time, she felt her comments were well-received by the other girls.

The group sessions were supposed to continue for several more weeks. But before their next meeting was set to occur, Molloy said staff members deleted their group chat and the meetings ended abruptly.

Two weeks later, she found out the group had resumed meeting without her. “It was the same girls — everyone except me.” Instead, Molloy was invited to have coffee with one of the women on staff, who tried to lecture her on what the Bible taught about homosexuality. “We would debate it over coffee,” Molloy said.

The lesbian former Cru staff member from Oakland University in Rochester who wishes to remain anonymous described being outed to her Cru supervisors in January of 2021 by a coworker. At the time, she had been involved with the organization since 2013.

Her supervisors presented her with an ultimatum. She could either come out as a lesbian to the entire team “for accountability” or step down from her position. She decided to walk away from Cru, and she came out publicly months later.

After coming out, she experienced rejection from the staff friends she had worked closely with for years. Some of them made direct comments to her about how they “could not continue to be involved with my life” and “would not support my relationship.”

“I was very lonely,” she said. “It’s been hard because these were people who, when they thought I was straight, would stop everything at the drop of a hat for anything I needed. They were the people who loved me better than anybody I’d ever known for my entire life, but it was very conditional on the fact that I was straight.”

Conversion therapy and sexual solicitation

Warning: This section contains explicit references to sexual acts.

On campuses in liberal-leaning cities like Detroit and Los Angeles, former Cru members say the organization is careful to avoid the topic of homosexuality.

Former member Nathan Bosak, a gay man from Pennsylvania, said he remembers one night at a Cru meeting while chatting with another member, he was told something he’ll never forget. “It’s not wrong to be gay, but it’s not okay to act on it,” the person said. A moment later they added, “I just wouldn’t recommend you even be gay though.”

Bosak said he had a good laugh and called it a day. But looking back, he said, “I will never forget that conversation. It’s going to live in my mind forever.”

In the Deep South, Cru’s attitude toward gay students can be outright abusive.

Matt Brewer, 35, grew up in an evangelical household in rural Mississippi. His parents put him through conversion therapy from age 13 through 16 via Reformed Theological Seminary in Clinton, Mississippi. He has little memory of those years because of how “heavily medicated” he was. When the conversion therapy didn’t work, his parents kicked him out of the house.

Brewer ended up attending Belhaven University, a private evangelical college, where he quickly became involved with Cru. At his first Cru event, he was introduced to the head of the campus’s chapter and nearly had an anxiety attack — it was the same man who had run Brewer’s conversion therapy.

Throughout his time at Cru, Brewer remained open about his sexuality. He said the backlash he received for his honesty was crushing.

“I was treated like I had the plague. I felt like I had a disease. I was somebody they were going to fix,” he said. “Gay conversion therapy was offered to me on multiple occasions. And it wasn’t expressly said, but it was implied that I could go there for free if I would just do it.”

In Cru spaces, Brewer said he always seemed to wind up in a room with an older man who “was trying to convert me, but trying to get my pants off at the same time.” He received countless explicit sexual comments and solicitations from men in Cru leadership. “It’s only gay if you suck it,” they would say to him. “Don’t you ever just need a release?”

He said he remembers one 40-year-old staff member with a wife and kids who told Brewer, “You just have to marry a woman and play the part. You can have your fun on the side — I’ve been doing it for 20 years.”

One night during a Cru retreat while sharing a cabin with a group of men, Brewer said he woke up to a 35-year-old man in his bed whispering, “You know this is what you want.” Brewer played football and weighed 250 pounds at the time, and he shoved the man off of him immediately. He told the rest of the group he’d had a nightmare.

“It was very confusing, to say the least,” Brewer said, “because here are all these people that were literally preaching about homosexuality and how bad it is, trying to get naked with another boy the same night.”

When Brewer complained to his female Cru friends about these explicit sexual solicitations, they told him, “Welcome to the club. They’ve been doing that for years.”

Leaving the fold

On a holiday weekend in 2009 while serving in student leadership with Cru, Brewer and his then-boyfriend decided to drive to Tuscaloosa and go to a gay bar. Shortly thereafter, Brewer was confronted by one of his Cru leaders, who had pictures of him and his boyfriend taken inside the bar. At the time, Brewer was 22 years old.

“It blew my mind,” Brewer said. “I took it very personally.” He demanded to know why the photos had been taken and by whom. The youth leader, who Brewer remembers only as Derek, replied, “You need to understand something, son. We have people everywhere… God is always watching.”

As punishment for “getting caught at a gay bar,” Derek took Brewer to the University of Southern Mississippi. He was tasked with picking up trash and cleaning toilets for a large Cru event so he could “learn to have a servant’s heart.” He said he remembers thinking, “This is borderline mind control.”

Brewer called his sister and asked her to pick him up. That same day, he said, he began quietly severing ties with Cru.

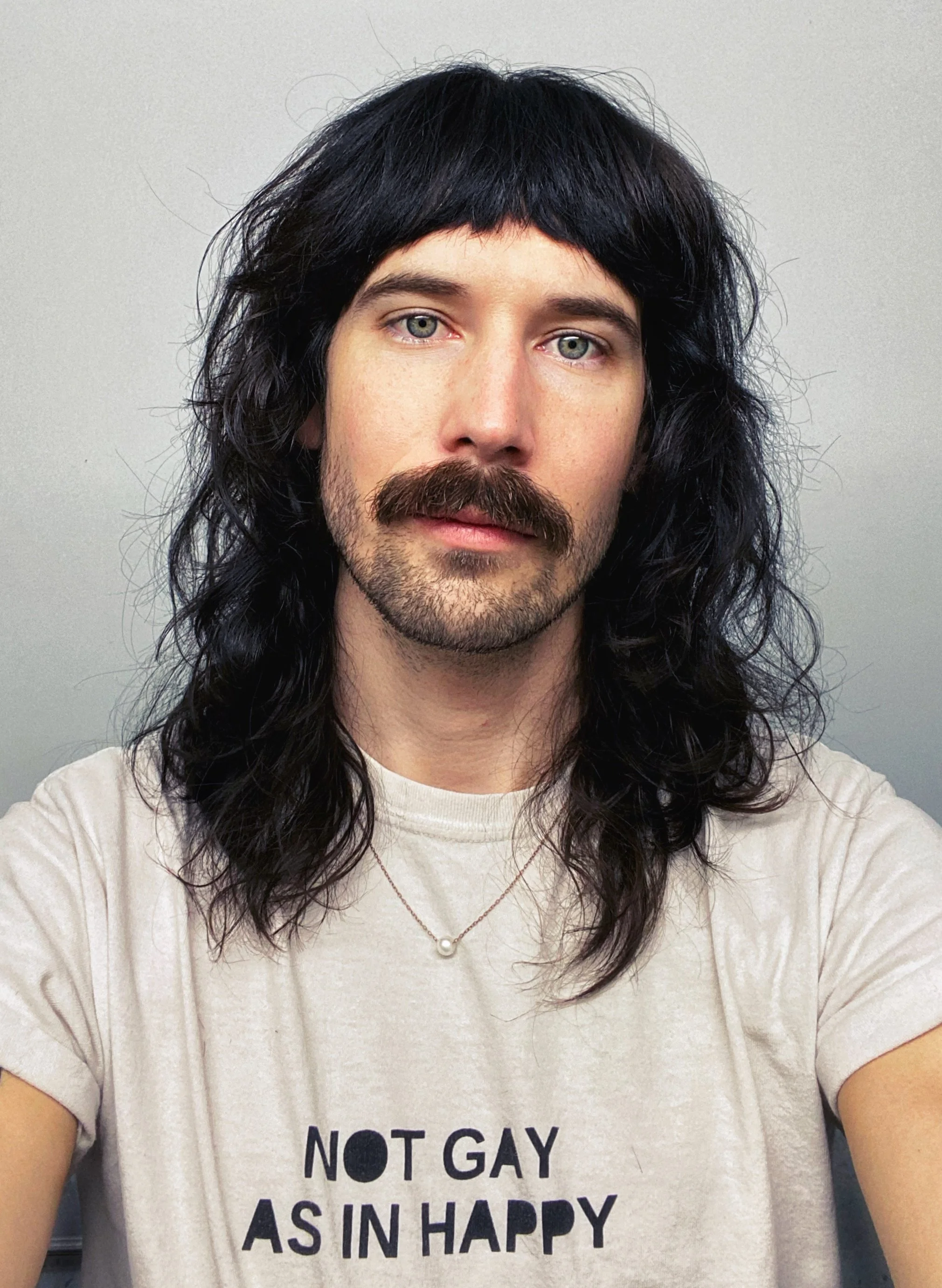

Zac Thompson said after years of mirroring their parents’ heavy involvement in the organization, leaving Cru behind felt freeing.

“That world felt so small,” they said. “The world my parents made for me — there was not space for nonbinary people, let alone agender drag queens. I’m all of those things.”

Interviews with former members suggest that Thompson’s feelings are shared by a host of students who also parted ways with Cru after becoming disillusioned with its approach to ministry.

Still, Cru continues to enjoy a strong presence on thousands of campuses across the globe. Its mission to “build and send Christ-centered multiplying disciples” has not changed, and it has never before faced public scrutiny, even for its treatment of the LGBTQ+ community.

Thompson said Cru forced them to sacrifice their own agency and autonomy for the sake of following Jesus. Cru taught them to spread the love of God to nonbelievers, Thompson said, but it neglected to teach them how to cultivate love and kindness for themself first. “It’s very conditional,” they said.

“To embody the values that Christ taught, I had to leave the church and leave all that to actually do what they raised me to do.”

Promotional flyer for a student protest at Rollins College spurred by a campus conflict with Cru. (Courtesy of Sianna Joslin)

Former member Zac Thompson currently works as an artist in New York City. They said much of their work focuses on “playfully expanding our understanding of gender, family, and home.”

(Courtesy of Zac Thompson)

Former member Matt Brewer said in Cru, “You cannot give the appearance of participating in sin, because you make the group as a whole look bad.” “Participating in sin,” Brewer said, would include being gay.

(Courtesy of Matt Brewer)

Former member Kiera Molloy said she has “done lots of healing” since leaving Cru in 2012. (Courtesy of Kiera Malloy)

During her time in Cru, Chelsy Albertson said she was “forced to be in discipleship” to address her “struggle with homosexuality.” She said the topic was “constantly talked about around me.”

(Courtesy of Chelsy Albertson)

Rollins student Kalli Joslin at a 2018 campus protest advocating for Cru to abide by the school’s nondiscrimination policy.

(Courtesy of Sianna Joslin)

Former member Rebecca Carey, who uses they/she pronouns, said Cru has “a very strict code of sexual ethics” that includes viewing being gay as a sin.

(Courtesy of Rebecca Carey)

George Mason University’s chapter of Cru provides resources on “homosexuality and the Christian faith” at the top of a webpage that lists “Support and Crisis Ministries.”

(Screenshot by Em Espey)

Listen to Matt Brewer recount the confrontation he had with a Cru staff member after being followed to a gay bar in Alabama.

“They were the people who loved me better than anybody I’d ever known for my entire life, but it was very conditional on the fact that I was straight.”

— Anonymous former Cru member and student from Oakland University at Rochester